Every year, thousands of migrants risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean Sea in fragile wooden boats, hoping to reach the shores of Europe. Many arrive on the Italian island of Lampedusa, where the vessels are left abandoned. In a prison on the outskirts of Milan, inmates are transforming those discarded boats into something unexpected: musical instruments. The post From shipwreck to symphony: Prisoners in Italy turn migrant boats into violins appeared first on The World from PRX.

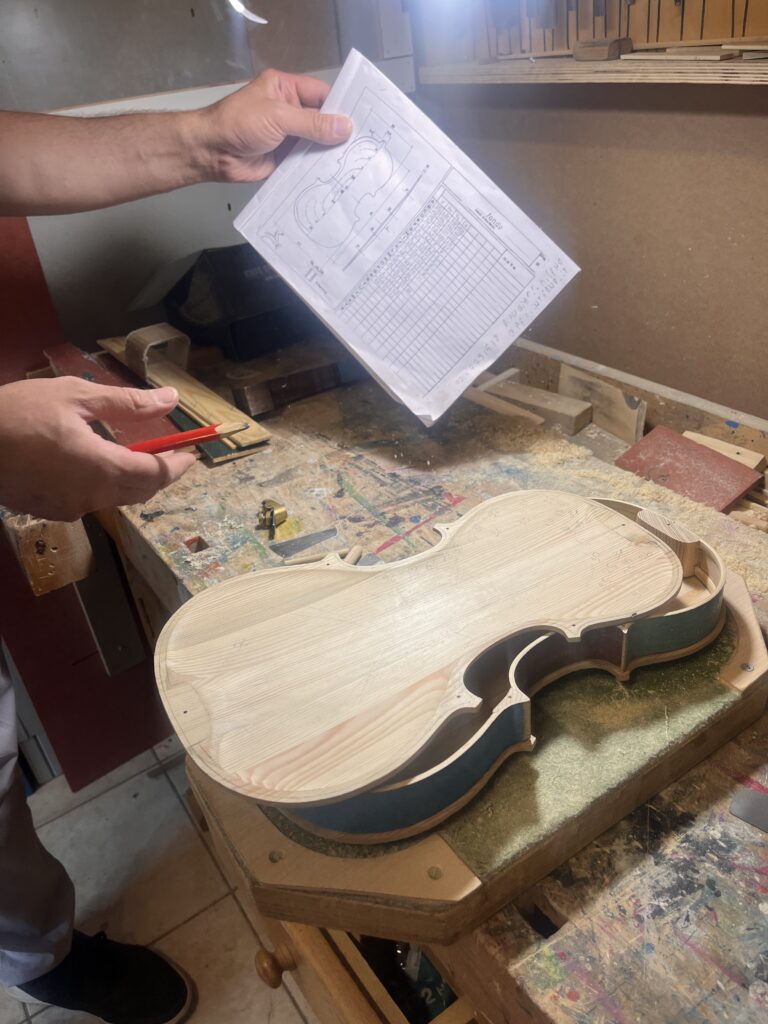

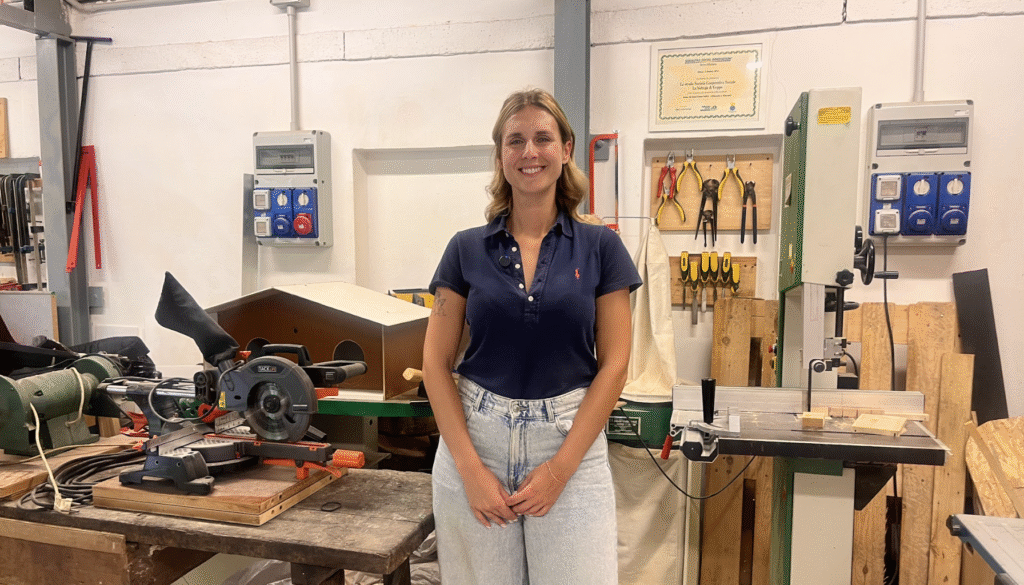

In a workshop in Milan, in northern Italy, Enrico Allorto, a master craftsperson known as a luthier, is bent over a bandsaw, slicing through a plank of wood salvaged from an abandoned migrant boat. At a workbench nearby, Nicolae, an inmate from Opera high security prison, is gluing narrow slats of the recycled timber together. Another former prisoner out on probation stands watching.

Nicolae, 43, who is from Romania is serving a 16-year prison sentence. He declined to go into details of his crime, and only shared his first name for privacy reasons, but is more than happy to talk about the hours he spends each day crafting instruments like violins and violas under the guidance of luthier Allorto. The work is slow and methodical. It requires patience, commitment and passion, Allorto said. Each instrument takes a couple of months to complete.

The brains behind the project they’re working on is Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori, president of La Casa dello Spirito e delle Arti — the House of the Spirit and Arts Foundation.

The organization first introduced workshops to make instruments in four Italian prisons a decade ago. In 2021, after witnessing the growing number of migrant boats arriving on the island of Lampedusa, Mondadori approached the former Italian interior minister with a proposal: to take the wood from those boats and use it in prison workshops. Greta Corbella, a spokesperson with the foundation said the minister agreed, even going so far as to offer to fund some of the transport costs of moving the boats from the island to the prison grounds.

The impact on some inmates has been profound, Allorto said. One former prisoner, originally from Ukraine, who wanted to remain unnamed also for privacy reasons, recalled how learning the craft offered him hope when he was at his lowest point.

“I was in a desperate situation when Allorto first approached me to join his workshop,” he said. Initially he had refused. At the time, he was confined to a wheelchair because of health problems and doubted he could manage the painstaking work.

But Allorto built him a custom-made seat and, little by little, he began to learn. Today, the two men are friends. The former inmate said he now hopes to turn his new skill into a full-time career — and a way to support his family.

Nicolae said it’s hard not to think about the migrants and what they had been through as he works with the wood salvaged from the shipwrecked boats.

“I know what it means to go to sleep as a child with a hungry stomach,” he said, adding that no one leaves their homeland and their roots to travel to Italy unless they’re desperate.

In February 2024, the project reached a milestone when 14 instruments made by the inmates were played by an orchestra at La Scala, the world-famous opera house in Milan. The ensemble, known as the Orchestra of the Sea, performed works by Bach and Vivaldi before a packed auditorium.

Nicolae, who was granted a temporary release from prison for the evening, sat among the crowd. He said it was the first time he had ever been inside such a grand theater. “I felt like I had won a battle — a battle with myself.”

Migrants who see the instruments played at concerts can become very emotional, Allorto said. “They see their suffering suddenly transformed into a thing of beauty.”

Modou Gueye, a Senegalese-born activist who runs a cultural center in the Corvetto neighborhood of Milan, said the initiative is important, not just for the inmates, but also for migrants. Particularly as attitudes towards asylum seekers in Italy have grown increasingly hostile.

“Before [Italian Prime Minister] Giorgia Meloni came to power three years ago, people wouldn’t openly threaten migrants or tell them to go back to their own countries. But that’s all changed,” Gueye said.

But he said that this initiative shows some people still care about the plight of asylum seekers. Gueye, who brings locals and migrants together through music and educational programs, said he hopes that one day, these instruments will serve merely as mementos of a difficult past — and not reminders of an ongoing tragedy that’s still happening off Italy’s shores.

Meloni’s far-right coalition government has refused to endorse the initiative. Greta Corbella with the House of the Spirit and Arts Foundation said she’s unsure if the government is opposed to the project or simply doesn’t care.

“They have shown no interest in the initiative,” Corbella said. For now the foundation has enough wood from migrant boats to keep going for a couple more years. If the wood runs out. then we will just continue with the concerts, she added.

The next challenge for the foundation is finding musicians and orchestras willing to take the instruments outside of Italy and play them on stages around the world. Master luthier Enrico Allorto acknowledged that the sound of the prison-made violins cannot match the precision of a Stradivarius — rare violins made by Antonio Stradivari, prized for their exceptional sound and craftsmanship. Musicians have to work harder to get the right notes, he explained.

“But musicians also understand there is something inside these instruments that other violins do not have — an emotion, and audiences can feel that emotion, too,” Allorto said.

The instruments contain the troubles of many people but they also contain beauty, he explained, and that’s something everyone can appreciate.

The post From shipwreck to symphony: Prisoners in Italy turn migrant boats into violins appeared first on The World from PRX.